The Selective Word Choice of the Legacy Media.

As the Twitter Files and the Missouri v. Biden free speech case showed, “fact-checkers” working for social media companies labeled content that was true but disfavored by the government as “misinformation,” or censored it outright. This has been an area of great concern to a number of independent journalists, with Matt Taibbi and Michael Shellenberger reporting on the Censorship Industrial Complex extensively.

Exposing this situation is an important endeavor. But a softer yet larger dynamic—the style-guide-enforced word choices of news outlets—arguably has more influence in shaping narratives in the traditional media, and it is much harder for people to notice or for journalists to expose.

Look at the screenshot of the homepage of the New York Times from yesterday.

Did you notice something specific about the headline?

Now look below.

Is the Times correct in choosing “militants,” over “terrorists”? A person’s or institution’s position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will of course influence the answer to that question.

But before we get to this specific word, some backstory on language use in media outlets. Words in news stories on inflammatory or complex topics are chosen very purposefully. News organizations have style guides that dictate such things as, for example, the use of Black, with a capital B. The use of militant in the Times’s coverage of Hamas is no doubt the result of a formal editorial decision-making process. It is not arbitrary. The editors know that word choice will be important in how this news story is framed for readers.

By choosing “militants” instead of “terrorists” the Times is not alone. With the exception of FOX, nearly the entire establishment media in America—including the Associated Press, the Washington Post, NBC, CBS, ABC, and PBS, among other outlets—in covering the events of the last two days all used “militants,” and secondarily “fighters,” “gunmen,” or any term except “terrorists.”

NPR was so committed to not using “terrorists” that it strategically went in and out of quotations while referring to a statement by Jonathan Conricus, an Israeli Defense Forces spokesperson [I added the bolding]:

“Our troops are still fighting and hunting down” remaining Hamas militants, Israel Defense Forces spokesperson Jonathan Conricus said, out of some 1,000 militants who “went house to house, building to building in search for Israeli civilians.”

The actual quote from Conricus was: “Our troops are still fighting and hunting down the last terrorists that are still inside Israeli territory… we assess that there were approximately 1,000 terrorists who participated in yesterday’s invasion of Israel. About 1,000 bloodthirsty Palestinians who went house to house, building to building in search for Israeli civilians.”

The NPR editors may view Conricus’s use of “terrorist” (and, for that matter, his use of “bloodthirsty”) as inflammatory and inappropriate, but it’s his language. It is telling that NPR not only won’t use the word terrorist itself, but chose not to allow its audience to hear the actual language spoken by a government official and make their own decisions about it.

But is the use of “terrorists” wrong? By assiduously avoiding that word, the Times and other legacy media outlets appear to be overtly going against the United States government’s definition of international terrorism and its view of Hamas.

First, the US Department of State lists Hamas as a terrorist organization.

Second, the recent actions of the Hamas members or those affiliated with Hamas appear to be, by definition, terrorism. The FBI defines international terrorism as “Violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups who are inspired by, or associated with, designated foreign terrorist organizations or nations (state-sponsored).”

Further, Chapter 113B, section 2331 of the US Criminal Code, from which the FBI distilled its definition, explains that these acts “appear to be intended—

(i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population;

(ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or

(iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping.

So every single element of what took place in Israel, according to the United States government, was the work of terrorists:

1) Hamas is a terrorist organization. 2) Its members or those associated with it committed violent acts. And 3) the acts—which included mass destruction, murder, and kidnapping—were aimed at a civilian population.

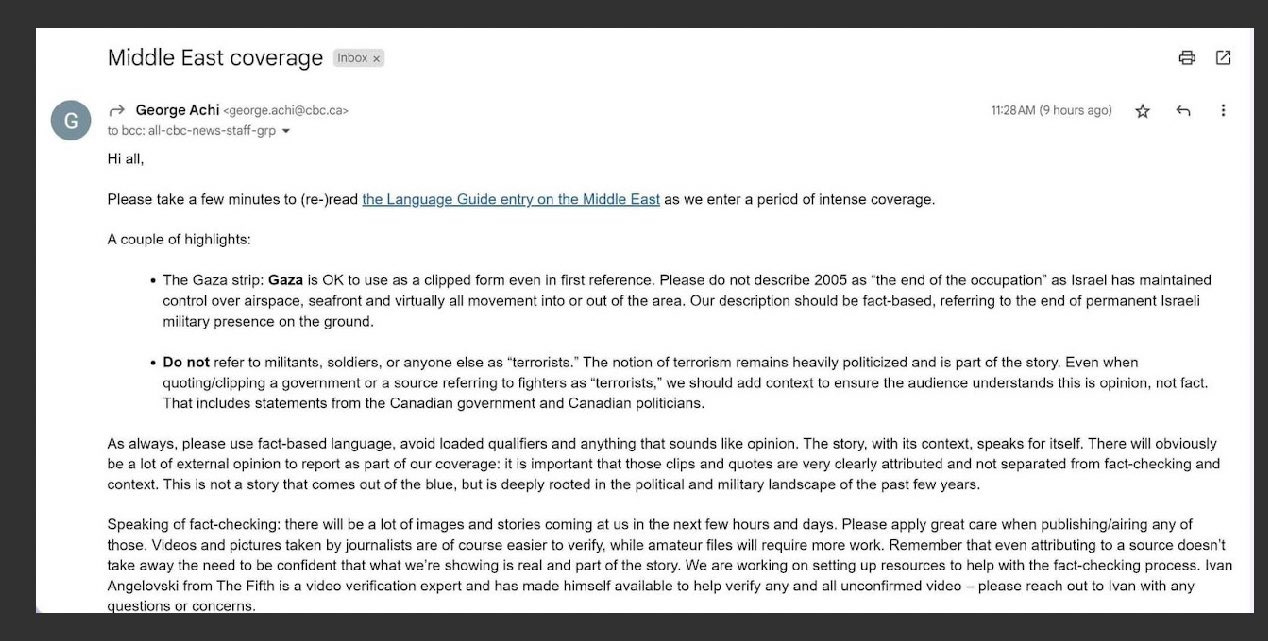

Canadian media is also following the same protocol. An unverified but apparently authentic email was sent by the Director of Journalistic Standards for the CBC instructing the staff “Do not refer to militants, soldiers, or anyone else as ‘terrorists.’ The notion of terrorism remains heavily politicized and is part of the story.”

Yet, like the US government, the Canadian government also includes Hamas on its official list of terrorist organizations. Hamas is “a radical Islamist-nationalist terrorist organization that emerged from the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood in 1987,” the government document explains.

To be sure, there is a lot of gray in the space of politically-motivated violence. One person’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter is another’s soldier. Militant is not wrong, per se. And as the Council of Europe notes, experts can disagree about what counts as terrorism. (Though it’s also worth noting that the Council says “terrorism involves deliberately targeting civilians,” which is what Hamas did.)

The media doesn’t have to follow the government line on any issue. Indeed, it should interrogate whether the government line is true or not. What’s worth considering, however, is that the legacy media, by and large, spent three years parroting the declarations of the CDC, Anthony Fauci and other officials about Covid and vaccines. Why did it follow the government in matters related to the pandemic, but not in matters related to the recent actions by Hamas?

More broadly, this semantic preference of the legacy media illustrates why X (formerly known as Twitter) is so important. Whether you agree with the use of “terrorists” or not, a social media platform that allows for unfiltered information enables citizens to see the world through many lenses, rather than through the frame—and, indeed, it generally is one frame by nearly all the legacy media outlets—created by a small clique of editors and journalists. As the podcaster and cultural commentator Konstantin Kisin wrote on this point, by using X “the way we receive and perceive information is much more meritocratic than before.”

“More broadly, this semantic preference of the legacy media illustrates why X (formerly known as Twitter) is so important. Whether you agree with the use of “terrorists” or not, a social media platform that allows for unfiltered information enables citizens to see the world through many lenses, rather than through the frame—and, indeed, it generally is one frame by nearly all the legacy media outlets—created by a small clique of editors and journalists. “

that’s it. thank you David!

"Attackers" is a less emotional word than terrorists, and in the immediate circumstance is a very accurate term. My pre-2000 copy of Webster's says a militant is one who is "fighting" or is "ready to fight, esp. for some cause."