NY Times Fact Check Fail on Excess Deaths - Part II

I continue to fact check the fact checkers, and things are even worse than they initially appeared.

Earlier this month the New York Times ran a “fact check” of the DeSantis-Newsom debate. Ironically, in what, alas, is now a pattern in much of the media, the fact check itself had a string of pretty bad errors—so bad that they showed the truth was the opposite of what the Times writers claimed. I detailed a bit of this in my last piece. All of the errors favored Newsom; you can make of that what you will.

One suspicious claim in particular, however, stuck out at me. And after some digging the story became much stranger than I expected. As a case study it exemplifies much that is wrong with journalistic practices, dovetailing with similar problems about sourcing and a lack of transparency that I exposed in an investigation of news coverage of the Gaza hospital explosion.

In the debate, DeSantis had said that “California had higher excess mortality than Florida,” which the Times authors declared was “misleading.”

The Times authors went on to explain:

During the two-year period of 2020 and 2021, Florida saw 183 excess deaths per 100,000 people while California saw 142 excess deaths per 100,000 people, according to an analysis by Andrew Stokes, a Boston University demographer, and Yea-Hung Chen, a University of California, San Francisco epidemiologist.

These numbers certainly would suggest that DeSantis was wrong. But how did the researchers that the Times cited arrive at this conclusion? No link was provided to this analysis so in an immediate sense it was impossible to know. I dug around and couldn’t find the presumed cited paper or report from these researchers, so I emailed both of the Times authors and the two researchers asking for information on this analysis. At the time of my post no one had replied to me. But a few day later I got an email from Yea-Hung Chen, one of the two researchers. That’s when things got weird.

Chen, an epidemiologist at University of California, San Francisco, said “the work is currently unpublished and unposted,” but that “related work” was going to be published in a month or so.

I wrote back asking that if the work was unpublished and unposted, how did the NYT reporters see the analysis? And I asked a second time to see the analysis. Chen didn’t respond so I sent a follow up where I summarized for him what seemed to be a bizarre scenario: a scientist at a public university conducted research, allowed only certain journalists to see it and then refer to it in print, and did not to allow anyone else to see it.

In what world was it appropriate for no one to be able to see Chen’s methodology, dataset, or any other details, but for the Times to refer to the conclusions of his analysis?

Chen replied that he didn’t think his analysis was unique and that the Times reporters hadn’t seen the underlying data either. Moreover, he said:

“I never ever viewed such comparisons as being super meaningful relative to the discussions people are having.” And that “the comparison of excess mortality between the two states is an interesting starting place, but. . . if somebody wants to seriously evaluate whether specific pandemic responses were effective, then I would suggest a different type of analysis.”

He ended by saying “you are not being singled out. I told a journalist from a large newspaper that I would not like to discuss the matter at this point in time. He respected my request, and I hope you will do the same.”

To recap: The Times cited an analysis to back up their claim that DeSantis was wrong for saying California had a higher excess mortality than Florida. The NYT reporters ignored my emails asking about the analysis. The researcher they cited acknowledged he shared the findings with the NYT of what is, essentially, a confidential analysis that he, nevertheless, believes is not meaningful or appropriate. And the researcher refuses to provide the analysis to, or discuss it with anyone else.

It’s hard to envision a more ridiculous case of opaque evidence used in a news article, let alone a “fact checking” piece that purported to refute a politician’s claim. It’s reminiscent of the Gaza hospital fiasco, insofar as none of the journalists—either time—would reply with evidence to queries about their sourcing. But this story goes a step further, in that when I reached the source, he, too, refused to share his evidence.

Chen and his partner’s analysis very well may be excellent, and methodologically well grounded. We have no way of knowing. But here’s what we do know:

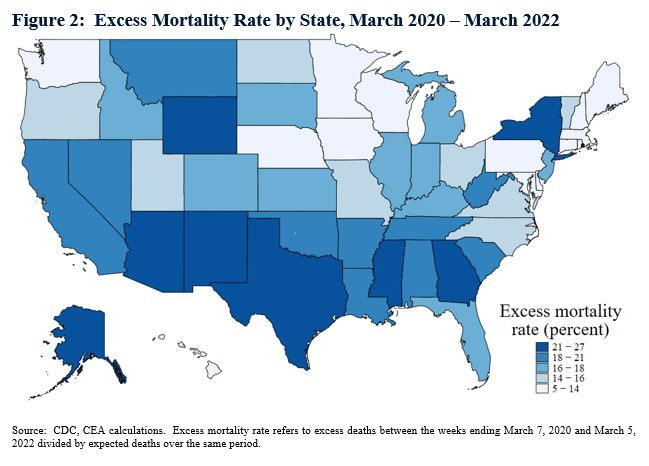

An analysis published by the White House came to the opposite conclusion of Chen’s secret paper. The graph below, from the White House, depicts excess mortality rates, by state, for a span of two years, from March 2020 to March 2022.

Forget about the X axis. For our purposes we’re not interested in percent uninsured. Looking just at the Y axis, it’s clear that California had a higher excess death rate for the first two years of the pandemic.

It’s easy to see on the map as well that California had a higher excess death rate than Florida.

Florida having a more favorable overall outcome from the pandemic than California is deeply inconvenient for a news outlet that lauded California’s more restrictive approach and demonized Florida as a “cautionary tale” of what happens when masks aren’t mandated and people go “barhopping.” But the evidence suggests otherwise. And journalists citing an unpublished analysis as a supposed rebuttal, that even the researchers refuse to share, needless to say, is not exactly persuasive.

" . . . the truth was the opposite of what the Times writers claimed." I was just going to type Yikes, but decided not to because this is disturbingly typical. Yawn is more like it.

I love your work, David.